In 1867, Congress criminalized the sale of oil that was made from petroleum. Mr. Dewitt was indicted for selling oil in Detroit, Michigan.

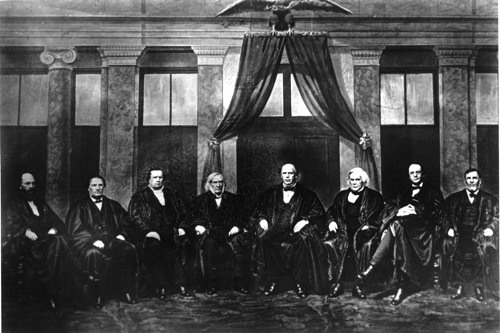

The Chase Court Court (1867-1870). Seated, from left to right: Stephen J. Field, Samuel F. Miller, Nathan Clifford, Samuel Nelson, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, Robert C. Grier, Noah Swayne, and David Davis.

![The Commerce Clause is a “virtual denial [to Congress] of any power to interfere with the internal trade and business of the separate states” except when it is a “necessary and proper means for carrying into execution some other power expressly granted or vested.”](https://conlaw.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1869-US-Dewitt-Chase-1-1024x576.png?v=1568566247)

The Commerce Clause is a “virtual denial [to Congress] of any power to interfere with the internal trade and business of the separate states” except when it is a “necessary and proper means for carrying into execution some other power expressly granted or vested.”

Employing Marshall’s construction from McCulloch, Chase concluded that this “consequence is too remote and too uncertain to warrant us in saying that the prohibition is an appropriate and plainly adapted means for carrying into execution the power of laying and collecting taxes”

Implied Powers on the Chase Court

In 1867, Congress criminalized the sale of oil that was made from petroleum—including transactions that were completed entirely within a single state. Mr. Dewitt was indicted for selling oil in Detroit, Michigan. His case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Chase wrote the majority opinion in Dewitt. He held that Congress’s authority under the Commerce Clause, by itself, was not enough to enact the stat- ute. Chase wrote that the Commerce Clause is a “virtual denial [to Congress] of any power to interfere with the internal trade and business of the separate states.” This passage echoes Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Gibbons.

However, there is an important exception to the rule.